Practice, memory, intelligence, talent… we can discuss these as much as we want, but I think that the most important element of musical training is motivation. People who are motivated to play music will practice regularly and get better at playing. If you’re good at playing, you’re going to want to do it more, which results in more practice. It’s a positive feedback loop. On the other hand, if you’re not motivated to play music, you won’t practice very much, and you won’t be good at it. This will not make you want to play more, and sets up a negative feedback loop.

External rewards

Practicing music is hard work for everyone, and we could all use external motivators from time to time. This is especially true for children. Getting “good” at playing music is a long-term reward and children do not have the self-discipline required for that kind of delayed gratification. So parents and music teachers offer incentives and rewards for practice: a sticker for a certain number of days or minutes of practice, a trip to a concert for a certain number of weeks of good practice. In my house, your daily piano practice will earn you 15 minutes of coveted computer play-time.

But it’s interesting and useful to consider what leads to motivation and why.

Reward centres in the brain

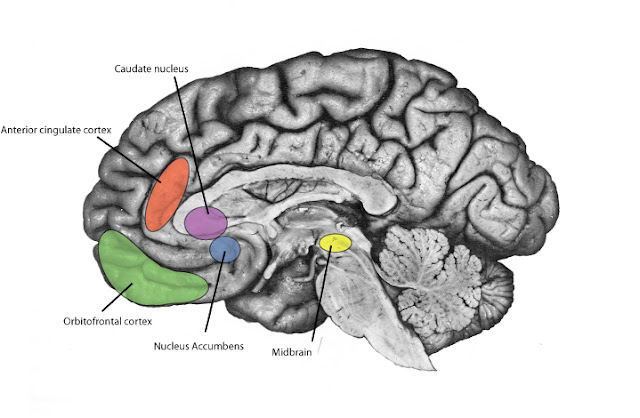

Rewards lead to activation in certain regions of the brain: there are reward centres in the midbrain, nucleus accumbens, caudate nucleus, and orbitofrontal cortex. These areas are activated by pleasurable stimuli: good food, money, sex, rewarding exercise, and listening to music we enjoy, among many others. These types of pleasures lead to the release of endorphins and other endogenous opiates, which activate the reward circuitry of the brain. These natural brain chemicals are related to drugs such as morphine, which explains why narcotic drugs also activate the pleasure centres of the brain.

Choice is a reward

A recent study published in the journal Psychological Science (Leotti & Delgado, 2011) reports that the ability to choose is a reward in itself. The anticipation of getting to choose something activates parts of the brain that are involved in the reward and motivation pathway. This study used a simple key-press experiment in which the participants sometimes got to choose which key to press, and sometimes were told by the computer which key to press. Pressing the key led to a random monetary reward, with the “choice” key-presses and “no-choice” key-presses leading to the same overall reward. However, the participants felt as if they were more rewarded when they got to choose which key to press. The researchers looked at which areas of the brain were activated during the key-presses and found that areas of the brain associated with reward were more activated when the participants got to choose which key to press.

The implication is that people see activities where they get to choose something as inherently more valuable than activities where they do not get to choose. We all like to feel we have control over our lives, as much as possible, and having that control activates the pleasure centres of our brain.

Choice increases the perceived value of whatever is chosen

Having a choice is motivating, but here’s a second point about choice that’s worth noticing: when we choose between two things that are similar, we are more likely to think that what we chose is even better than we first thought. This was first shown in the 1950’s by a researcher who asked housewives to rate kitchen appliances, and then choose between a pair of them. When later asked to rate the appliances again, the housewives had increased their preference for the appliance they selected, and decreased their rating for the appliance they didn't select.

This “choice-induced re-evaluation” has been shown repeatedly in different studies. In 2009, Sharot et al. showed that after people had chosen something (in this study it was a hypothetical choice of vacation destination), there was an increase in activity in the caudate nucleus, an area of the brain implicated in motivation and reward. This meant that after choosing something, they derived even more pleasure from it.

How can we apply the power of choice in musical training? Motivation is a critical element of musical training. Any way we can increase motivation, we should take advantage of it!

Use the power of choice

As teachers and parents, we can take advantage of the power of choice to increase students’ motivation. Parents can give students the option of when to practice, and in what order. Teachers can let students choose from a list of two or three pieces when selecting repertoire. This opportunity to choose is a reward in itself and also will make the students like the chosen piece more. As we have seen, it will be natural for them to re-evaluate the piece as more pleasurable once they have chosen it. If students start out liking the piece more, they will practice it more. The more they practice, the better they get at playing it, and this makes them like it more, setting up the positive feedback loop that we’re looking for.

After musing and reading about choice as a motivator this week, I realized that this is actually a fairly common tool in a parent’s arsenal. Right now my 6-year-old is going through a phase of aggressive rebellion (at least, let’s hope it’s a phase). Recently, I convinced him to get into the bath but when the time came to wash his hair, he absolutely refused. “I got wet all over and that’s good enough”, he insisted. Instead of fighting, I played the “choice” card: “Would you like Mummy’s shampoo, or Daddy’s, or here’s a new kind that’s passionfruit flavour. Mmmm, it smells good”. It worked like a charm to defuse the power struggle. He was happy because he got to choose, and he liked the fruity shampoo even more once he had chosen it.

This week, I'll offer him a choice in his piano repertoire and I’m willing to bet he’ll like to play whichever piece he chooses. I can almost see his caudate nucleus lighting up.